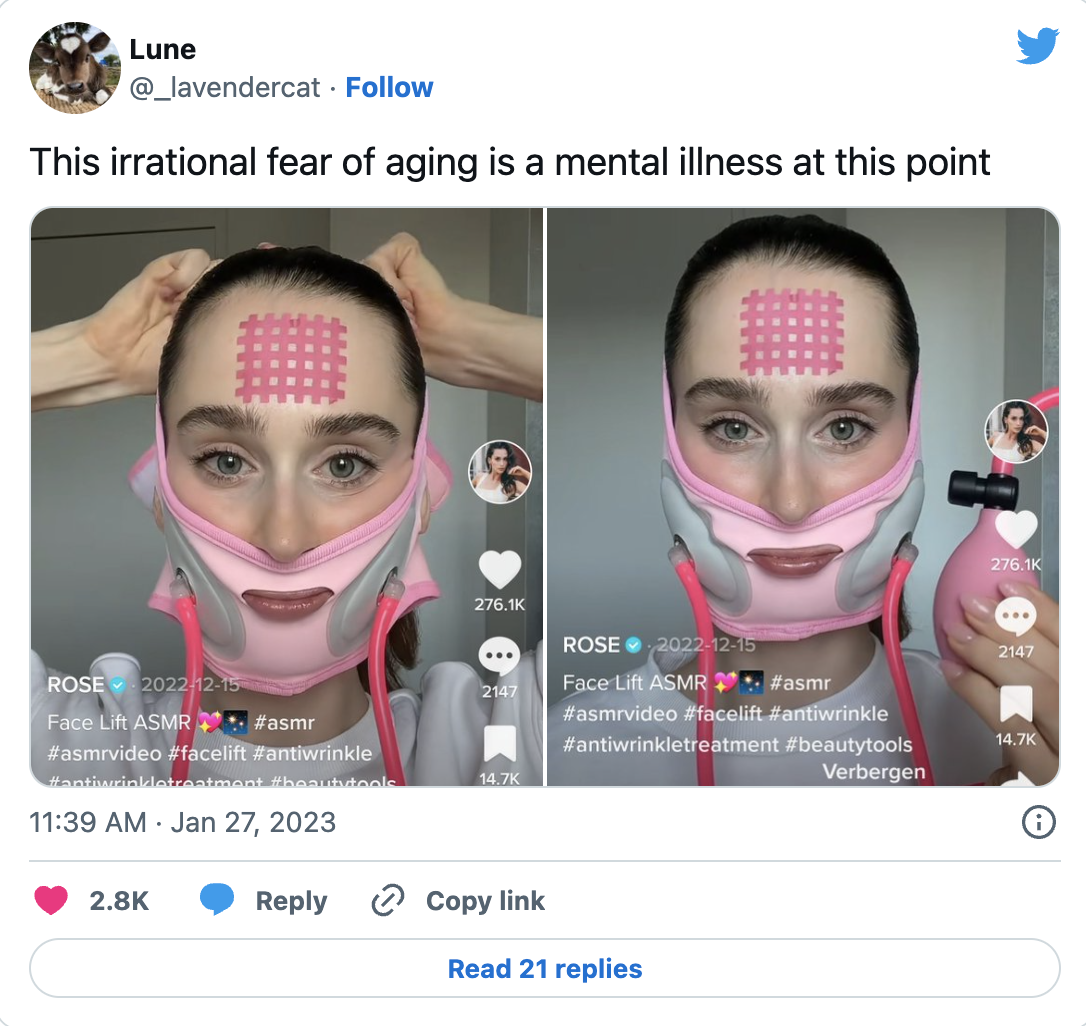

Over the past 12 months I’ve been keeping a list of all the things that I am supposed to do in pursuit of a beautiful, lineless face (no, really – that’s the link to my actual list). A few standouts among the 35 line items include: start ‘baby botox’ at age 22 to prevent evidence of growing; buy an ‘anti-wrinkle’ straw for sipping drinks; tape my face to make my nose ‘skinny’; sleep on my back – not for health benefits, but so my face doesn’t become asymmetrical.

Maybe ‘supposed’ is too strong of a word. It is being suggested that I do these things. The suggestions come from corporations, media, the growing contingent of dermatologists, estheticians, cosmetic nurses and plastic surgeons on social media, and very often from other women, whether they’re celebrities, influencers or just everyday people.

The advice is well-meaning, of course. It’s just there in case I want an improvement to my face, so that I will look ‘good for my age’ or ‘not my age’ in the future when signs of that age will inevitably become a problem. I am an interesting, kind, smart, fun person to know (self-confidence platitudes are a perky accomplice to the advice), so it would be a shame for lines and jowls to obscure my inherent value as a human being.

But while the instructions of beauty are free, the implementation is not.

There are only two commodities in life: money and time. Usually, you get to choose – pay with one or the other, depending on which you can afford to spend. The pursuit of beauty is unusual because we have to pay with both. We’re paying in dollars, apparently USD$250,000 on average across a lifetime. Often forgotten is that we also pay with time. Precious seconds, minutes, hours and hours and hours spent in front of a mirror, in a chair or bed, driving to and from appointments, hiding out in downtime from more aggressive treatments or surgeries.

Sure, there is always more money to be made (is what I say when I buy myself a little treat) but you can’t really earn time back. It’s used once and forever. Look, this isn’t science but my back-of-the-napkin calculation has a modest skincare-brows-makeup-hair-appointment routine at 10,556 hours over a lifetime. What do most men spend those 10,556 hours doing? According to Malcolm Gladwell, it’s enough time to become an expert at something.

What we are offered in exchange for those payments of time and money is protection.

Under the patriarchy, conformity to the beauty standard is safety. The pretty privilege girlies don’t want you to know this, but the further you are from The Beauty Standard the worse everyone will treat you – the system and the individuals within it. Less opportunities, more harassment; less consideration, more violence. The halo effect of attractiveness is well-documented.

This is the sticking point where discussions about feminism in beauty always get tripped up. Who am I to denounce other womens’ defense mechanisms from patriarchy and white supremacy? Camouflage makes you less of a target, sharpening the knife makes it hurt a little less. If decorating your cage brings a morsel of joy even as it dissolves your own feathers, then you might as well do it – we’re not getting out of the cages either way. Unadorned bars are not freedom.

Sable Yong writes about the idea of beauty being a meritocracy in her newsletter Hard Feelings, one where the value is “undercut by the effort made to achieve it.” It’s how we decide who deserves protection or comfort from the worst harms of patriarchy – you earn safety by conforming to the system. Just like capitalism where the more money you have the easier things get, so it goes with patriarchy and the merit of beauty.

This lets the Beauty Industry creep up to position itself as the great equalizer. As a tool putting some agency and equity in the hands of those not born genetically blessed,helping us get closer to The Standard that will afford some power and protection. If you’re not born into wealth, you can (allegedly) work for it. If you’re not born into a wealth of looks, you can work to pay for those too and get a boost up the ladder.

The problem with the concept of the beauty industry as a tool of equality is… it doesn’t work like that at all. It’s a profit-hungry machine that only serves to further entrench the inequalities that already exist among women.

Philosopher and ethicist Heather Widdows suggests there are four dimensions of beauty – youth, beauty, thinness and whiteness – and patriarchal expectations mean you are only allowed to fail at one. While you can buy fixes for any of the four dimensions, it should not be a surprise that the most transformative, protective beauty treatments are only attainable to the wealthy.

Gender-affirming surgeries for trans women are one example; a trans woman’s ability to ‘pass’ as a biological female can be as much for safety from threats, attacks and harassment as for feminine beautification. When TikTok personality Dylan Mulvaney underwent facial feminisation surgery less than a year after coming out (absolutely good for her), other trans women pointed out how lucky she was – the procedure is expensive, difficult to access and out of reach for less privileged women.

Where poor people must make do with pharmacy-brand concealer, the rich can get under eye filler or a face lift. Attempts to contour away an ethnic nose with makeup are unconvincing; the wealthy can have a perfectly petite, white nose constructed directly onto their face.

Class and wealth intersect with all other dimensions of oppression, including gender, which is why beauty can only ever be a modest tool of empowerment, but never a tool of liberation. A woman who visibly ages or has drooping eyelids or allows her face to change is still viewed as having committed a moral failure – she did not work hard enough to afford the solution to her beauty problem, like her wealthier peers were able to.

It’s at this point I have to do the uncomfortable thing and point out our own culpability as women. We are crucial soldiers in upholding patriarchy; we enforce stricter and stricter, higher and higher, evermore inconvenient standards on each other. Our exemption from responsibility crumbles whenever we invent – entirely on our own – new ways to raise the bar.

No matter how many times I have heard “I’m not saying you have to do this, this is just what works for me” as a disclaimer from a woman on social media, it has never felt genuine. Be honest, did you start taping your own mouth closed because you thought it looked like fun? If it makes you feel better, why?

Patriarchy includes women who intentionally shift the goal posts. Who re-draw the limits of The Standard smaller and smaller each time, careful to keep themselves at the centre. Who refuse to interrogate why they like what they like, or why a woman’s lips are supposed to look like that.

It would not be fair to have written this essay without confessing my own State of Face. My routine is minimal: it can be so thanks to genetics, it must be so because I legitimately cannot afford any more than that. Independent media isn’t a lucrative business. But ten years ago, with even less financial stability than I have now, I spent amounts I’d rather not think about on Fraxel lasers and facials and expensive creams.

These transformative-and-conformative treatments were not attainable to my mother and her family or the women in my father’s family as new migrants to Australia in the 70s. Mum will turn 60 in a couple of months – she looks like herself, a face that I love. I feel sick at the thought of her ever looking in the mirror and feeling upset at what she sees, although I know that sometimes she does. At 33, sometimes I do too. I feel even sicker at the thought of having ever contributed to her feeling that way, although I know I must have. How must it feel to watch a younger version of yourself try to erase some of your shared features from her face? How does it feel to watch others correct on their faces the things you see on yours? Go online, to encourage even more women to do the same?

I’ve been crying while I write this (a cringey thing to admit, but cringe is the theme of the moment so I don’t care). The pressured pursuit of beauty has made all women cry, even those crowned Most Beautiful, Most Sexy, Most Wanted. It makes us cry and it tells us we’re worthless unless we’re trying to be hotter and robs us of our cash and worst of all, our time. We never get the protection or power that’s been falsely promised. If we have to participate that’s one thing, but at the very least let’s not call it feminist. Let’s not call it empowering. Let’s refuse to escalate the standards. Let’s not tape our faces.

Return to issues